The general notion is that there are individuals who incline right, left, or center in terms of their political and economic ideological inclination. However, on the contrary, these terms cannot be thrust into silos as conceived before this century.

How did the three afore-mentioned words even come to be? In laymen’s explanation, this phenomenon spurred up during the French Revolution. In the Assembly of the People, generally the representatives that supported the monarch sat together in the right of the aisle, while the ones opposed sat on the left.

In a broad spectrum, it could be generalized as—the ones on the right are conservatives, inculcating the ethos of aristocratic and imperial rule, while the ones sitting on the left—advocate for a progressive change, a new mechanism of governance, and societal transformation (they did not represent the periphery of the society, as argued by Marx).

As students of history may well know, the French Revolution is one of the many failed revolutions of the past, which resulted in greater instability and continued constitutional crisis, resulting in the French Republic being in its 5th inception—”The Fifth Republic.”.

Ideologies are in a hasty change; their evolution is imperative.

The very crux of the political spectrum as we know is being redefined at this very current juncture in time, from the traditional left and right divide to, as Tony Blair suggested, between the sides that support an open society, with engagement in technological innovation, pluralism, global cooperation, immigration, and most importantly, the free market principle. However, the other lot adhere to the idea of a more closed-off society, with protectionism in terms of trade, cultural hegemony, viewing immigration as a poisonous venom, reduction in innovation, and the perception of going back to the “good old days.”

To better understand the recent phenomenon, it is vital to know the massive shift that took place three decades ago—resulting in an astronomical transition to a new global order—the order tangled with hardened political and economic implications.

After the fall of the Soviet Union in the year 1991, for the first time after the Roman Empire—there was a global hegemonic superpower, the United States, a title not even obtained during the peak of the British Empire, due to competition amongst European adversaries in the global space.

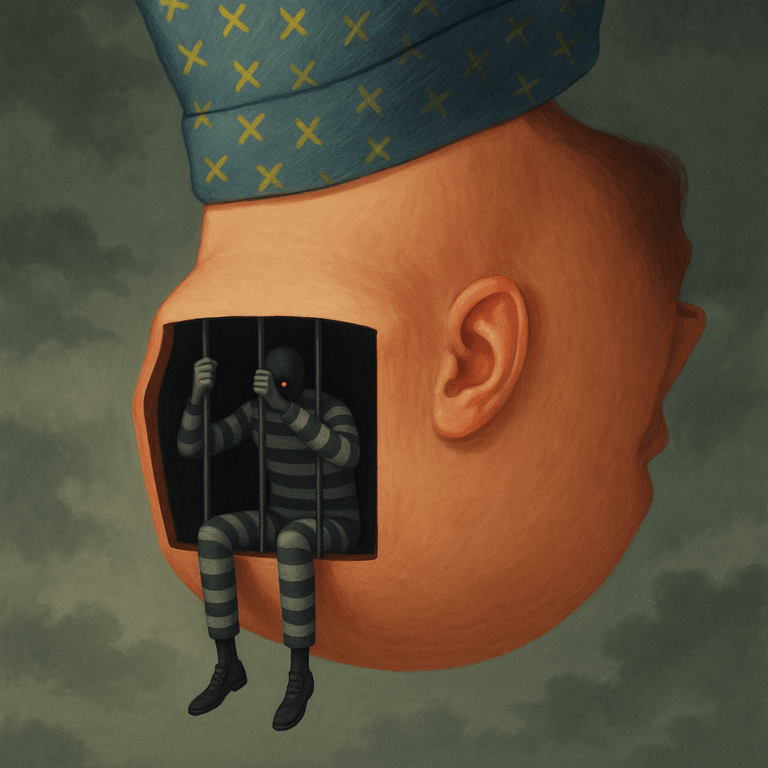

A superpower does not constitute only having the sheer muscle power; conversely, a distinct way of governance. For example, one of the two superpowers during the Cold War period, the Soviets modeled themselves on the Communist doctrine—ideas engulfed between that of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and Khrushchev (leading the de-Stalinization effort). All in all, it transpired to be a society that empowered its citizens with neither political power nor economic power—both were controlled by the state, or in colloquial terms, the higher echelons of the Communist Party—the Politburo.

On the other hand, the opposite ideological project led by the United States was completely contrarian to that of the Soviets. It empowered its people with political and economic freedom in togetherness.

With the freedom of electing your representative, participating in civil society, freedom of thought, and expression in terms of politics (one could argue the curtailing of these very factors during McCarthyism, also known as the Second Red Scare), while in terms of economics, the liberty to rise in terms of wealth as much as you would like—enabled through deregulated markets, emboldened by the nitty-gritties of capitalism, promotion of greater involvement from an agrarian society to participation in the service industry, and investment in the financial world, from stocks, bonds, and real estate, domestic or foreign. Imagine exercising all these very undertakings in the USSR, in a society where what and how much you consume is also decided by the state. A state as such is destined to fail.

Rather than dilly-dallying. The world had two choices, the Soviet Communist Model and the American Capitalist Model—it is quite evident while concluding which one of the two triumphed at last.

The revolutionary phase led to the book The End of History and the Last Man written by Francis Fukuyama, where it is argued by him that the fall of the Soviets has led to the end of ideological evolution, and the universalization of Western liberal democracy is the final form of government.

To some extent, right after the following period, there was an expansion of the liberal order, from democratic expansion in Eastern Europe, Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia, each embracing the rudiments of this very way of politics—multi-party elections, civil liberties, and market-based economics. While all this, multilateral organizations also grew in tandem with the growth in membership of NATO and the European Union, all incorporating recently transitioned liberal democracies.

During this great global transition, a major powerhouse was emerging: the previously self-titled “Middle Kingdom.” Its project of opening up the markets—giving economic freedom to its people—proved to be successful; for the global world, a swath full of opportunities opened—with greater interconnectedness in the global economy, a level never reached before.

But the rosary story would not last for long. The first challenge to the American-led order came from a security and cultural angle—the September 11 terrorist attack.

The war initiated by Al-Qaeda and other fringe Islamist groups upended the global security parameter; coincidentally, during the same period, personal computers appeared at most middle-class homes, with rising popularity of Windows and the dot-com bubble—entering the era of the “Internet.” The attack led to the greatest surveillance effort, a project that still continues, and countless military offensives that turned out to be a military, cultural, political, and social blunder.

The overuse of American hard power fermented dissent. The hoax regarding weapons of mass destruction in Iraq propagated by the Bush Administration reduced trust in the political system. The Iraq and Afghanistan campaigns brought out debate regarding the military industrial complex at the forefront. The 2008 Financial Crisis reduced the credibility of the American Financial System—a model that was also revered by America’s ideological foes.

All in all, the beginning of the new century marked the start of a slow and steady process of democratic decline.

Just in two decades, there is the overturning of the global order, intense globalization, technological revolution, and cultural revolution. Conversely, with all the fruits of success the ideal system brought—the advantages of it did not trickle down to most, and most important, the change of all aspects of life was too drastic to comprehend, and backlash to the multifaceted revolutionary measures was inevitable.

The rise of populist leaders all around the globe, whether they give their allegiance to the right or left of politics—one thing is common: they serve as reactionary forces to all the aforementioned changes in the world. From disdain towards free markets to skepticism of technological innovation, rejection of cultural inclusion, i.e., immigration. The overall notion is that from all this change, you the people have not benefited, the Asians have taken your degrees, the Hispanics have taken your jobs, and the blacks are killing your children.

The epitome of the current phenomenon is ethnonationalism intertwined with economic protectionism and, essential of all, the rollback of American domination of the global system.

Juxtaposing the abovementioned with what Tony Blair said, the new ideology is not about left wing or right wing; it is if you believe in an open society or a closed society ranging from economic, social, and political.

In simpler terms, the new political spectrum could be redefined as, do you wish to go back in time or progress in an inclusive democratic liberal global world?