For a frequent reader of my treatises, it may have been evident that my abstraction towards progress and continuity is by and large riddled with positivity — even if it may sound hyperbolic at times — but nonetheless, a sense of precarity towards India persistently creeps into me.

On the one hand, I tend to gravitate towards pronouncing a doomsday-esque situation whereby the country has no hope by virtue of the intrinsic ethos that had been denoted previously by me as “Contemporary Feudal Aristocracy”; though, on the other hand, the Socratic nature in my demeanor succumbs me to probing into the nuances that permeate in a society, albeit generalized presupposition is counterintuitive to any process of logical deduction. Which is why, rather than being inundated with the vitriol-like events that may spur nihilistic tendencies towards the prospect of a behemoth — India — let’s take a bird’s-eye view.

For a starter, the nation is very complicated. To be precise, it is a civilization. And sadly, her inhabitants today — her people — inculcate a vapid realization of the vastness, both in a literal and figurative manner.

Apologies for the consequent inundation of facts (something that is hollow in this day and age).

ON A SIDE NOTE:

The lores of the many gazillion GODs will be left for the self-professed enlightened blokes to enumerate; they are the purveyors of religious fanaticism, which largely serves as a hangover of archaic ideas.

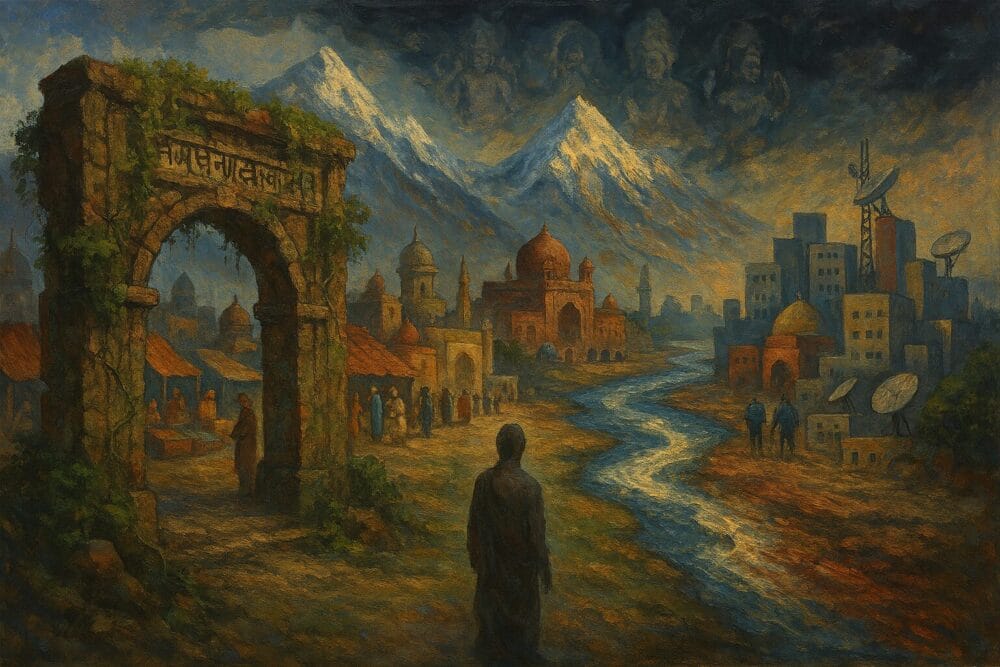

To begin, from the Indus to the West, the Himalayas to the North, the ocean to the South, and the Mountains of Southeast Asia to the East lies a civilization that has spanned over eons and makes for a peculiar shape on the global map, making it distinguishable amongst the many places. Recently — in this epoch specifically — diversity seems to be a professorial neologism trumpeted by many in the recent past; yet, India, though never a unified nation institutionally per se, was and continues to remain a collective society where diversity is not merely a political talking point or an endeavor, but a living reality.

From the ancient city of Taxila, where ancient Greeks intersected and even at times shared intimacy with the up-and-coming Buddhists or the already established Hindus, who were by no stretch of the imagination distant from the contemplative faculty commonly derived from the Platos and Aristotles of the world, in fact, similar to the Greco manuscripts, Indian theologians and thinkers drenched themselves in pondering about our reality, often times deducing along the similar lines of demarcating that, after all, our physical reality may well be an illusion; correspondingly, in Vedanta philosophy, such is denoted as “Maya,” literally meaning illusion.

Not to mention that once, as denoted in the book “The Golden Road,” an Indian religion, Buddhism, was adhered to by a majority of the global population. As we are now privy to, it was not just a religion confined to the peripheries of modern-day China; it was, in effect, a way of life that found its comfort from beyond the Indus, to Sumatra, to the Korean peninsula, and also in the halls of the Chinese Empress Wu Zetian, who had advisors, courtiers, and confidants as monks hailing not from a Chinese city but from the Buddhist monasteries in modern-day Bihar, such as Gaya — where Buddha had been enlightened whilst meditating under a tree.

Certainly, with the passage of time, there are a litany of instances that may well ignite a sense of wonderment towards anyone, like it has to me. That said, the many churns in the past are not purely a vestige of the past. Quite the contrary, for India, at its current juncture, it should serve as a moral calling, or in other words, spark a sense of not only historical nostalgia towards ways in which India landed its mark on the world, but also evolved over an extended period of time, above all, markedly, posturing a resolve that was and should continue to be bounded with a sense of resilience coupled with progress in plurality — not via the means of parochial dogma.

To further make sense, referring back to my previous lamentation, the country at the moment can, by certain scientific metrics, be deemed as being on the cusp of an “emerging economy,” “powerhouse,” “world power,” and et al. Such rhetoric does not appease me, especially when one with their naked eyes is startled by the dismal state of economic, social, and political affairs.

Synonymous with other nations, in this epoch, India is facing issues that have resonance in many body politics; it actually bore witness to populism before continental Europe, or the Americas even imbued it into their vernacular. Social toxicity, which is to say, the visceral hatred towards the other religion, was an impulse that was in hiding — only by the virtue of a secular state apparatus that ultimately got diminished by the turn of the century. Such an impulse — of unsolicited hate — has engendered credence from institutions and the overarching public parlance on novel forms of media.

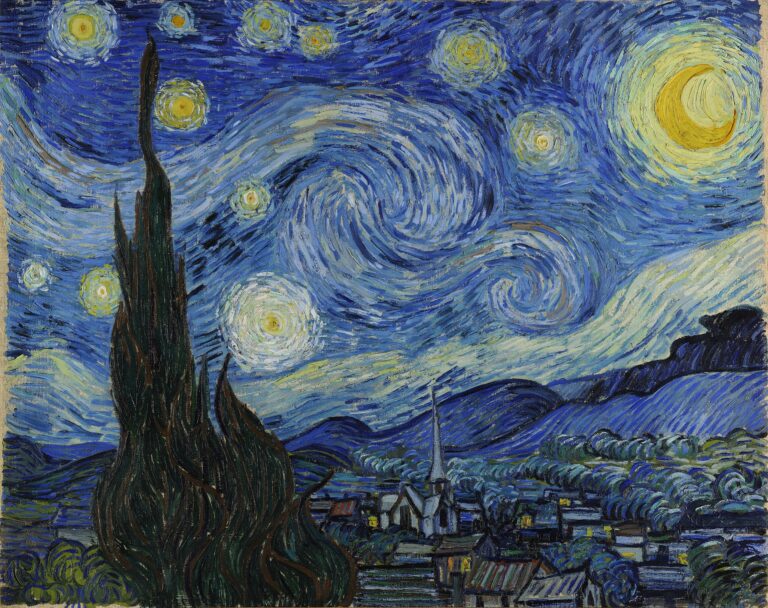

Paradoxically, there certainly is a reason for my constant incantation, which, suffice to say, is the beauty of the nation. It alludes to hope. Lately, whilst reading David Brooks, he hypothesized his postulation towards America’s predicament as a phase of “rupture and repair.” Likewise, 1.4 billion people cannot be outrageously disregarded; such is just pure arbitrary and vacuous, to say the least.

Therefore, connoting the two complex ideas (not nation-states), on the one hand, the idea of America as envisioned by its founding fathers and other forthcoming visionaries, and on the other hand, the idea of India, grounded on the philosophy from eons and the recent strife of Mr. Gandhi.

Equally, both the nations are on the cusp of a rupture; such is normative in any one strand of time, be it personal life, where we call it ups and downs, or, for that matter, civilizations now require a change that outmatches the denigrative upheavals, bluntly speaking, a renaissance that gives a potent antidote to cynicism, grievances, and despair.

In short, the vastness of our civilization does put an Orwellian type of situation as hyperbolic. When you get right down to it, capitulating everyone to your whims is an ordeal that never sees the light of tangible accomplishment; the challenge is not just a struggle against a singular dispensation or ideology; albeit, we just find ourselves to be part and parcel of a timeframe where greater undertaking is required for justness to saturate, or as Mr. Gandhi said, “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.”