Democracy is a farce if it is fiddled with paleolithic institutions and an inchoate civic virtue. Such that, apologies for the lack of a euphemism, the rise of the global south is, plainly speaking, wishful thinking. The rise of such nations per se is largely predicated on a growing population. Though, not on a strong social fabric that is conducive to progress, be it in terms of progress in emancipating the mind of archaic dogmas or progress in making a more advanced economy by the virtue of education.

In the recent past, this region of the world, in particular, has engendered a great disdain for their respective dispensations, largely by the up-and-coming adolescents, who find themselves to be the dominant demographic in many of these places, or, for the sake of the lack of a better term, these populations are young, coupled with a general absence to actualize individual upward mobility.

Such vociferous-laden resentment has amalgamated sentiments to reach a high degree, thereby making anarchical transgression, or in other words, taking matters into their own hands (the youth), a norm.

Without the intention of pontificating, simple solutions to convoluted structural qualms usher in greater doldrums.

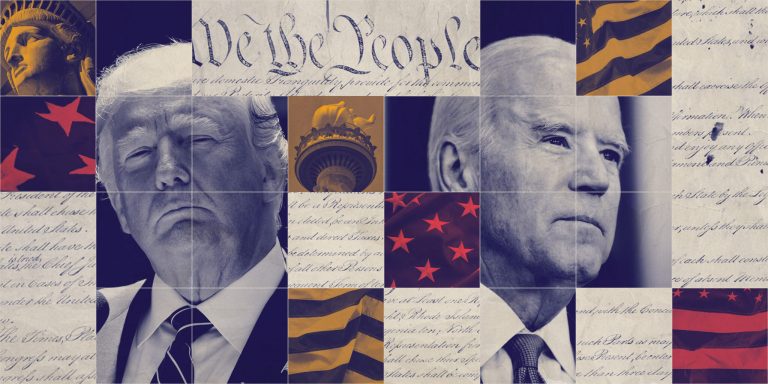

The world as a whole has seen a multitude of tides; over the past 100 years there have been successive changes in the zeitgeist, from a longing for totalitarianism when the Soviets seemed to have caught the consciousness of many, to neoliberalism subsequent to the riches amassed after unfettered markets, and now populism — a backlash against everything, be they the cultural, economic, social, political, or technological changes that took place in the preceding timeframe.

Keeping the Arab Spring at bay, populist backlashes in the Global South have taken shape in a differing way; rather than having a sophisticated political movement curated via a partnership with the intelligentsia and grassroots civic organizations — a broad framework that is more pronounced in the Western Hemisphere — it is nonexistent in nascent democracies in the developing world.

The void of coherence and plainly vengeance-seeking exemplifies distress towards society writ large; however, more importantly, at the end of the day, the societal fabric in such places is not congenial to the idea of having a liberal democracy.

Why is such the case? In all likelihood, since a liberal democracy was and continues to not be thought of as an ideal, or in another sense, a project that is pluralistic in nature, in extension, democracy does not imply furthering feudalism, a cultural attribute that is in continuum in the global south, especially in the Indian subcontinent.

That is to say, I like to postulate these societies as places where the broad notion of a “democracy” is underpinned by a feudal aristocracy. For the many folks who may not grasp what I am positing, rather than me rummaging through mundane instances, a quick search pertaining to the formation of the higher echelons of places, namely, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal, will elucidate a striking fact—all political outfits are spearheaded by families.

Besides, adding to the above-mentioned, the idea of family first percolates to the private sector. In the global market, one can name numerous private entities stemming from China and inevitably a gazillion from the United States. I reckon doing such with the subcontinent would be an insurmountable hurdle. As a result, systemic impediments to actualizing wealth-making block the riches that a free market should bestow upon the citizenry, albeit enabling it to be hoarded by a cabal of crony feudal lords, be they the family scions of political outfits or conglomerates.

Only a sporadic eureka moment amongst the plebiscite as a whole can pivot a deeply rooted cultural attribute. Till then, democracy, liberalism, and the impulse of imagining a new region catalyzing a new global order are, above all, hocus-bogus.