We—the people—collectively have reached a pinnacle moment—entering the final year of this century’s first quarter. Whilst this span of time since the year 2000, a massive upheaval transpired: From the pervasion of personal computers; exposure to a new immersive world— “the Internet”; the most interconnected we have been, both in reality and in tandem in the virtual world; ultimately, upliftment of billions from abject poverty.

Conversely, for a litany of times, I have reverberated in this blog the evident schism that prevails on this cusp of time—a division, me versus them—may it be on the basis of one’s race, creed, culture, color, religion, and gender, with explicit adherence towards the dogmas of tribalism, nativism, and nationalism, alas, spewing of dog whistles that propagate the idea of “othering,” which is the antithesis of a cohesive global community (liberal in the conventional sense is a discussion for another day).

As a result, it is palpable that many may and do possess the tenets of pessimism towards not only getting ahead but also getting by both socially and economically—leisure is an addendum—which suffices to say one avails in meager instances.

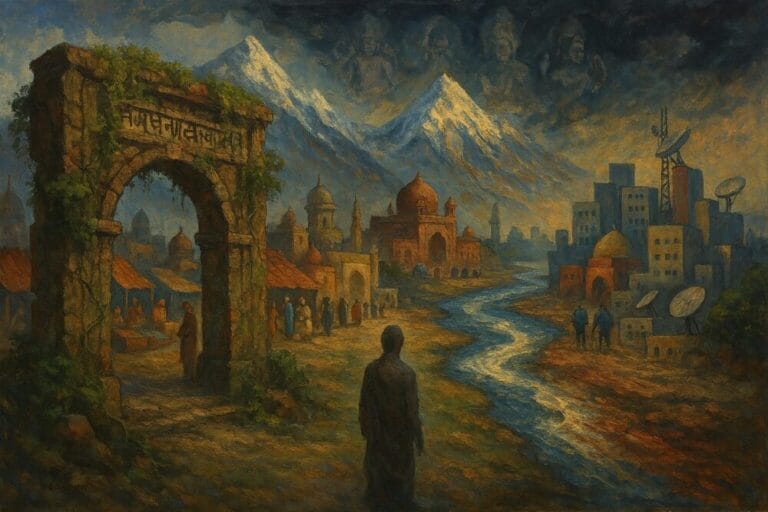

Since the inception of my blog, I have been writing pertaining to politics, economics, and social phenomena—on the basis of what I read from other pieces of work: For the likes of books, articles, academic journals, and lectures; nevertheless, they are inapt whilst comparing it to first-hand anecdotal experience; therefore, during the winter break, I visited India—a country I myself was disillusioned from its political status quo—as I would say “ossified from the perilous state of the most fundamental aspect of a society—its politics.”

During the span of a month, I observed the happenings of a nation-state, which, to my eyes, is a project that is a testament to the very substratum of what failure implies when connotating it with nation building. My very first experience when stepping foot in the nation was distressing, from the ghettoization of religious minorities to a lack of professionalism in the know-how of how an international airport of the capital city should operate—the sense ambiguity is furloughed in the mind of a foreigner.

Thereafter, while commuting in the cities of India, each and every one will be enlightened with the fact vis-à-vis the identity of the ruling dispensation, with the face of the Indian Prime Minister thrust in every nook and corner of a street; moreover, saffron flags placed by the ideological guru of the BJP—the RSS—a group that is a proponent of the idea that the Indian subcontinent (Akhand Bharat) in totality belongs to the “Hindus” and exerts its dogmatic Hindutva decrees amongst the masses. Two trends are inevitably clear from the aforementioned instances: First, there seems to be no space for a political opposition to the BJP; if there is, they might be shoved in the periphery of social media. So… is India a one-party state? At the moment it seems as if it is the case. Proxies of the ruling party have infused themselves in a multitude of aspects of life, from sports societies to religious institutions. Speaking of places of worship—second, religious fanaticism is at its ultimate in India; on a personal note, I felt obnoxious from the perpetual religious cacophony peddled on television and in the streets by self-proclaimed individuals of righteousness—acharyas, priests, astrologers, and God-men. Likewise, people inculcating a tad bit of scientific temperament and pragmatism gauge for a leeway in which they can instantaneously leave the country at all costs—the political demagoguery in India has percolated the dictum that nepotism and corruptions triumph over natural aristocracy—a merit-based society.

Whenever there is a general discourse regarding the state of an economy or even its poverty state, differing types of statistics are stated, such as GDP, GDP per capita, urban/rural population, consumption patterns, tax collection on the basis of the brackets, unemployment data, and digital penetration; consequently, for India, many with all the wit and exuberant confidence may proclaim the extraordinary efforts of poverty eradication, or along the lines, however, it is needless to say the situation is on the contrary; in actuality, a singular datum is plausible enough to distinguish the denigrative state of poverty: 800 million people receive free grains from the Indian Central Government, or in other words—53% of the population; half of the inhabitants are unable to amply reap the basics of human survival—GRAIN. If such is the predicament, policymakers, rather than liberalizing the minds of people, have succinctly made it homogeneous—filling it with ethnonationalism intertwined with xenophobia towards different castes, cultures, creeds, colors, and religions, such is the case in a country as eclectic as India, which, on the basis of estimates, has 1.5 billion people; 22 official languages; 19,500 dialects; 2,000 distinct ethnic groups; and a cultural tapestry that includes over 4,000 years of recorded history.

The current state of affairs is incomprehensible to both a pessimist and an optimist.

If the current trends consistently follow until her centenary—2047, the prevailing situation will need not subside but rather exacerbate; many will suffer, whilst the ones who can afford it will find a new life in a civilized nation-state, which at the least can provide its citizenry basic amenities and treat them as competent, decent citizens—not second-class citizens; even in some cases, ironically, cows are the privileged in a society embroiled with religiosity.